Memento Mori

Memento Mori

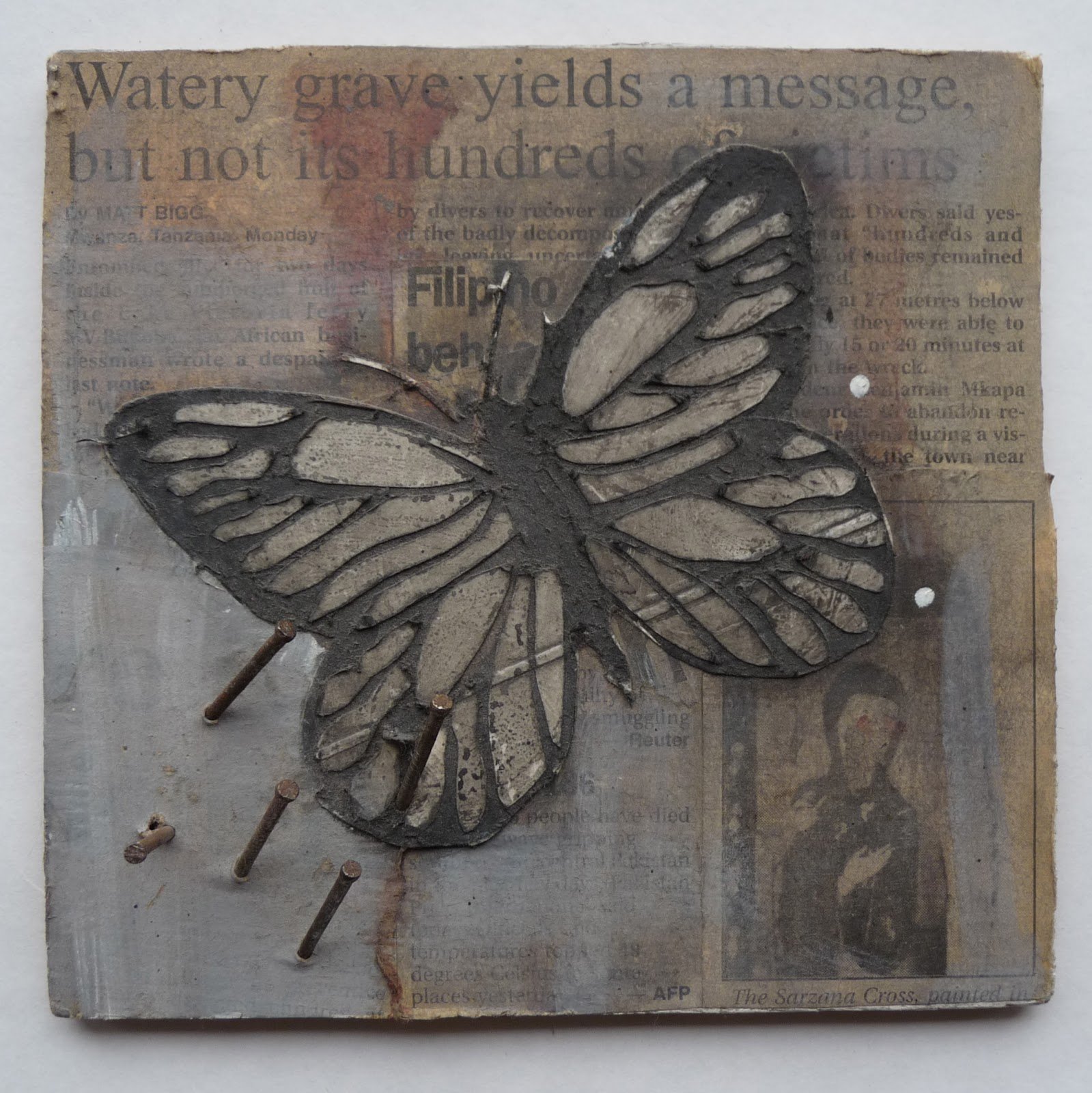

“Death…it is an unavoidable part of life. Yet in modern human culture it’s a taboo subject, discussed only when necessary, and even then usually only in hushed whispers. Americans, in particular, are devoted to perpetuating the fantasy that you can stay young forever and live indefinitely, the narrative of eternal life scribed by theologians, who now pass the torch to transhumanist futurists and Big Pharma.” - The Occult Museum

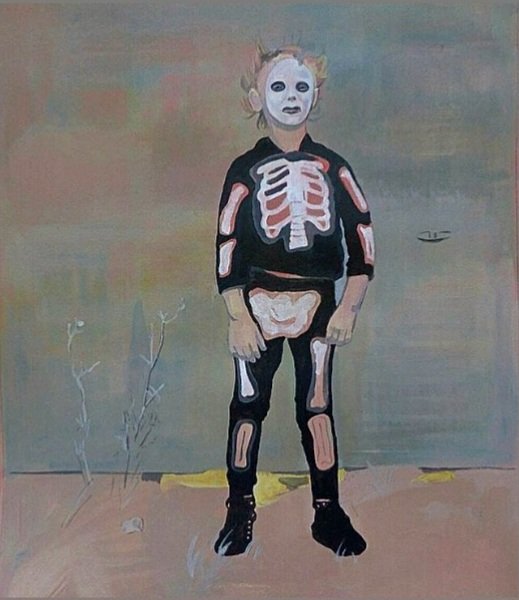

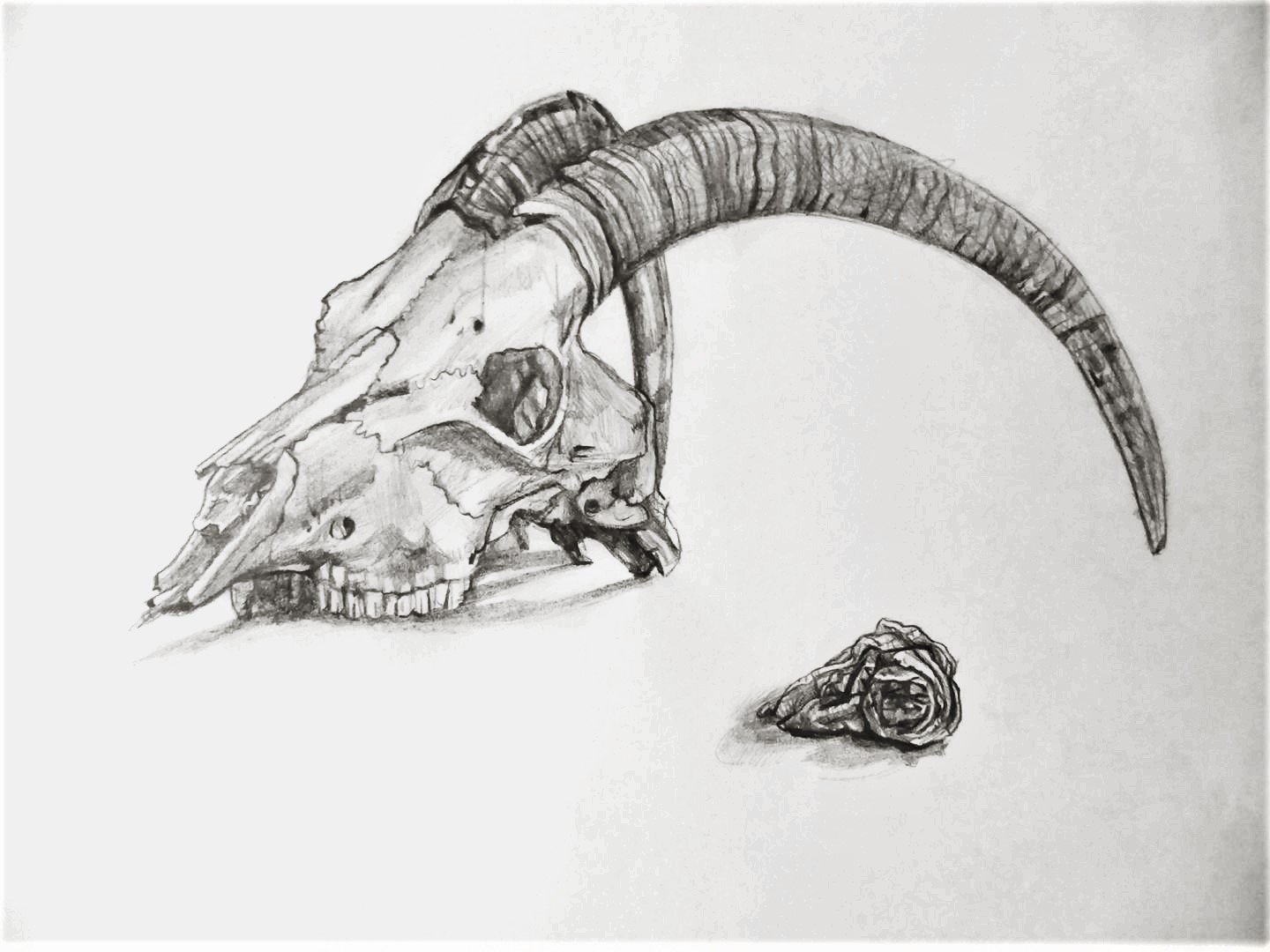

Memento Mori is a philosophical term that reminds us of our transience on Earth, and serves as a warning to prepare ourselves for whatever other realm awaits us.

A memento mori is an artwork designed to remind the viewer of their mortality and of the shortness and fragility of human life. These pictures became popular in the seventeenth century, in a religious age when almost everyone believed that life on earth was merely a preparation for an afterlife. A basic memento mori painting would be a portrait with a skull but other symbols commonly found are hour glasses or clocks, extinguished or guttering candles, fruit, and flowers. - TATE Gallery

This current body of work is an exploration of this somewhat antiquated tradition of mourning symbolism

During the Victoria era the reality of death was embraced and the deceased was often immortalised by means of post-mortem photography and mourning paraphernalia.

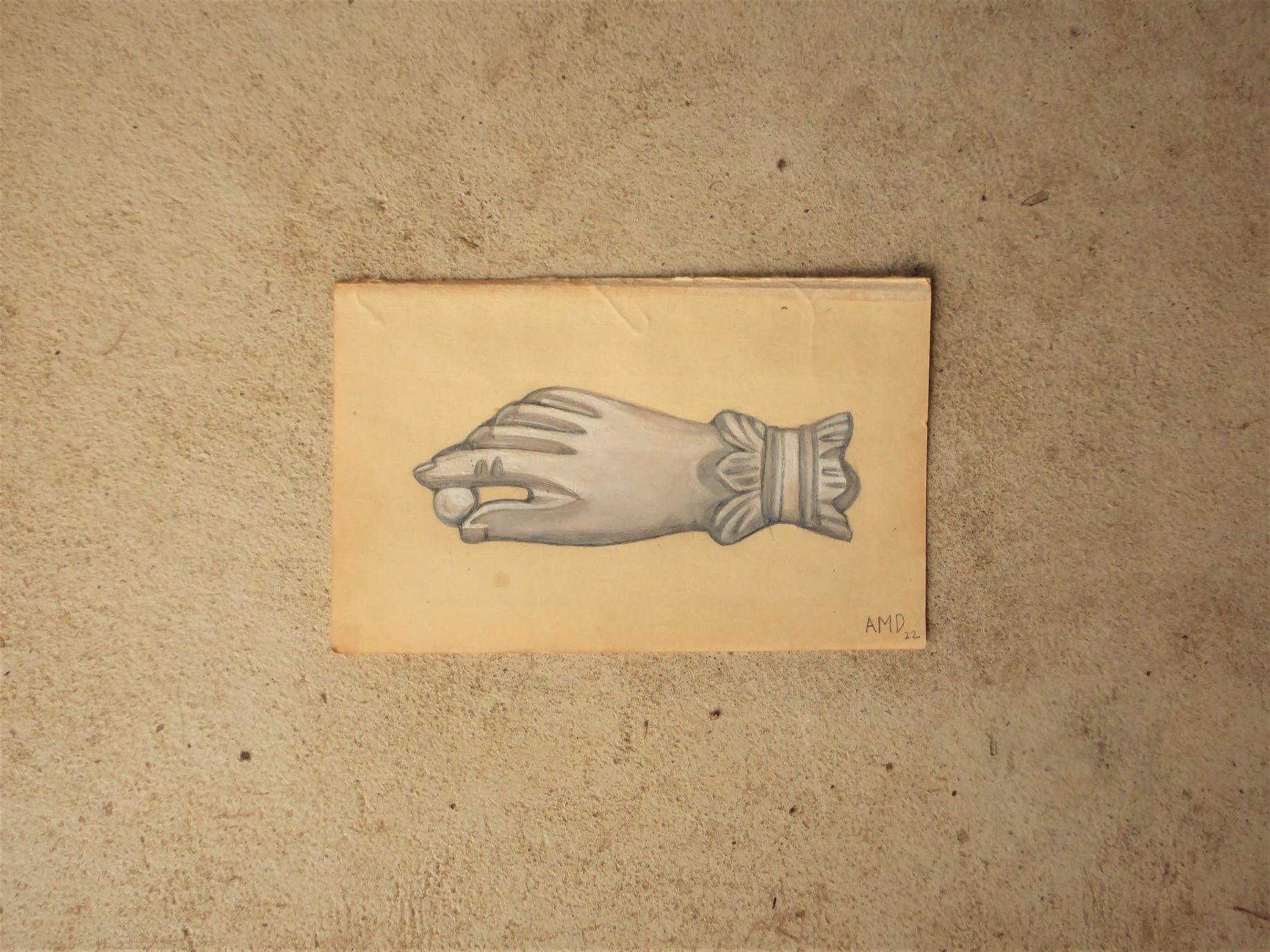

Victorian Mourning Jewellery is most often associated with the Victorian period, popularised by Queen Victoria’s very public mourning after the death of Prince Albert in 1861.

For the next 40 years, until her own death, Queen Victoria wore nothing but black, and commissioned special jewellery pieces to commemorate Albert, as well as other beloved family members who had died, such as her mother and daughter, Alice. Many of these pieces were made from black stones like jet and onyx, and some incorporated a lock of hair or a photograph of the deceased, which were all design elements that became popular among the masses, though many opted for cheaper black materials like black glass (‘French jet’), enamel or vulcanite.

Mourning pieces weren’t necessarily all black, though, with surviving examples commonly incorporating agate, pearl, garnet, human hair, ivory and gold, making for some truly striking and beautiful items. Pearls were often incorporated into the jewels made to remember children as they symbolised tears, while white enamel was used to remember children and unmarried women.

Mourning jewellery pieces that have been passed down through families and survive to this day commonly feature an inscription, the initials of the loved one, a knot motif (often woven from hair), a small portrait photo or painting, or a silhouette of the deceased. Mourning jewellery can come in many different designs, but are most commonly brooches, rings, lockets and sometimes hair or tie pins. They will often feature strong symbolism such as crucifixes, flowers (especially the forget-me-not and the turquoise colour associated with this flower), angels, clouds, mourners sobbing at tombs, urns and weeping willows.

Perhaps the most characteristic of Victorian mourning jewellery is the use of human hair, often woven into intricate patterns or even to depict miniature scenes. It was also commonly braided into the chains that held watches or pendants. Victorians believed that human hair contained the essence of a person, and therefore had a sacred quality. It symbolised the deceased loved one’s essence, as well as immortality, since the hair survived long after the person is gone.

Interestingly, it was not only the hair of the loved one that was incorporated into memorial jewellery. At once stage during the Victorian era, England was importing 50 tons of human hair every year for the mourning jewellery industry, to supplement the strands provided by grieving family members. - Traces Magazine

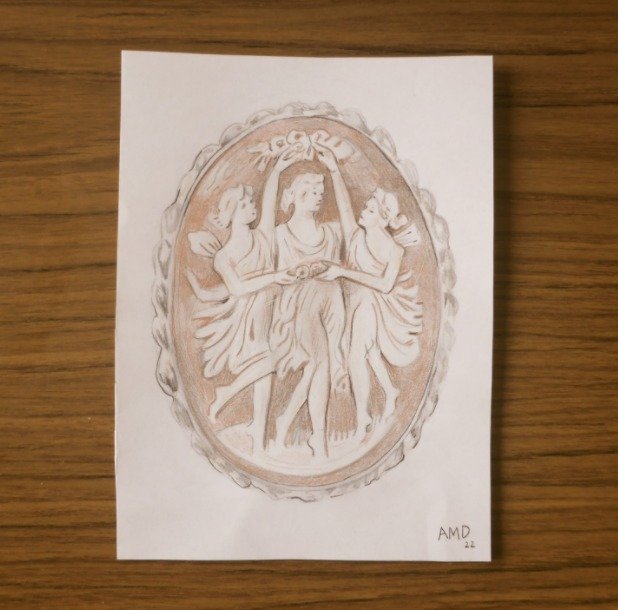

The Three Graces

The Victorians were fond of sending covert sentimental messages hidden in flowers, gemstones, and cameo carvings. This tradition began somewhat earlier, during the High Renaissance, period but can be traced back through antiquity. The Three Graces or Charities were a popular theme of the Hellenistic revival through the late 18th century; their association with mourning can be gleaned from the below paragraph:

“All that we have to remember is that the bounty bestowed by the gods upon lower beings was conceived by the Neoplatonists as a kind of overflowing (emanatio), which produced a vivifying rapture or conversion (called by Ficino conversio, raptio or vivificatio) whereby the lower beings were drawn back to heaven and rejoined the gods (remeatio). The munificence of the gods having thus been unfolded in the triple rhythm of emanatio, raptio, and remeatio, it was possible to recognize in this sequence the divine model of what Seneca had defined as the circle of Grace: giving, accepting and returning.” Pagan mysteries in the Renaissance. Edgar Wind 1958

One of my favourite Renaissance Philosophers and an influential Humanist, Marcilio Ficino, also wrote: “All the parts of the splendid machine (machinae membra) are fastened to each other by a kind of mutual charity, so that it may justly be said that love is the perpetual knot and link of the universe: amor nodus perpetuus et copula mundi.”

"It's so sad that we don't understand that each moment of our lives– drinking coffee, walking down the street, reading the paper– is it. Why don't we grasp this truth? We don't get it because our little minds think that this second that we're living has hundreds of seconds that preceded it, and hundreds of seconds still to come. So we turn away from truly living our life."

–Happiness and How it Happens, Charlotte Joko Beck

Modern society has a difficult relationship with death. As a young woman and trained grief and loss volunteer support worker, I spent many years supporting families with terminally ill children - using the arts to assist the journey of parents and siblings through the illness and death of their children or siblings, to honour the memory of those who had passed through remembrance ritual, and to assist in processing and releasing their grief. Many of these families were isolated by their experiences of death - alienated and dispossessed by society.

In The Denial of Death, a book which I am currently reading, Ernest Becker writes: “Man is out of nature and hopelessly in it; he is dual, up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill-marks to prove it. His body is a material fleshy casing that is alien to him in many ways—the strangest and most repugnant way being that it aches and bleeds and will decay and die. Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with atowering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot and disappear forever.”

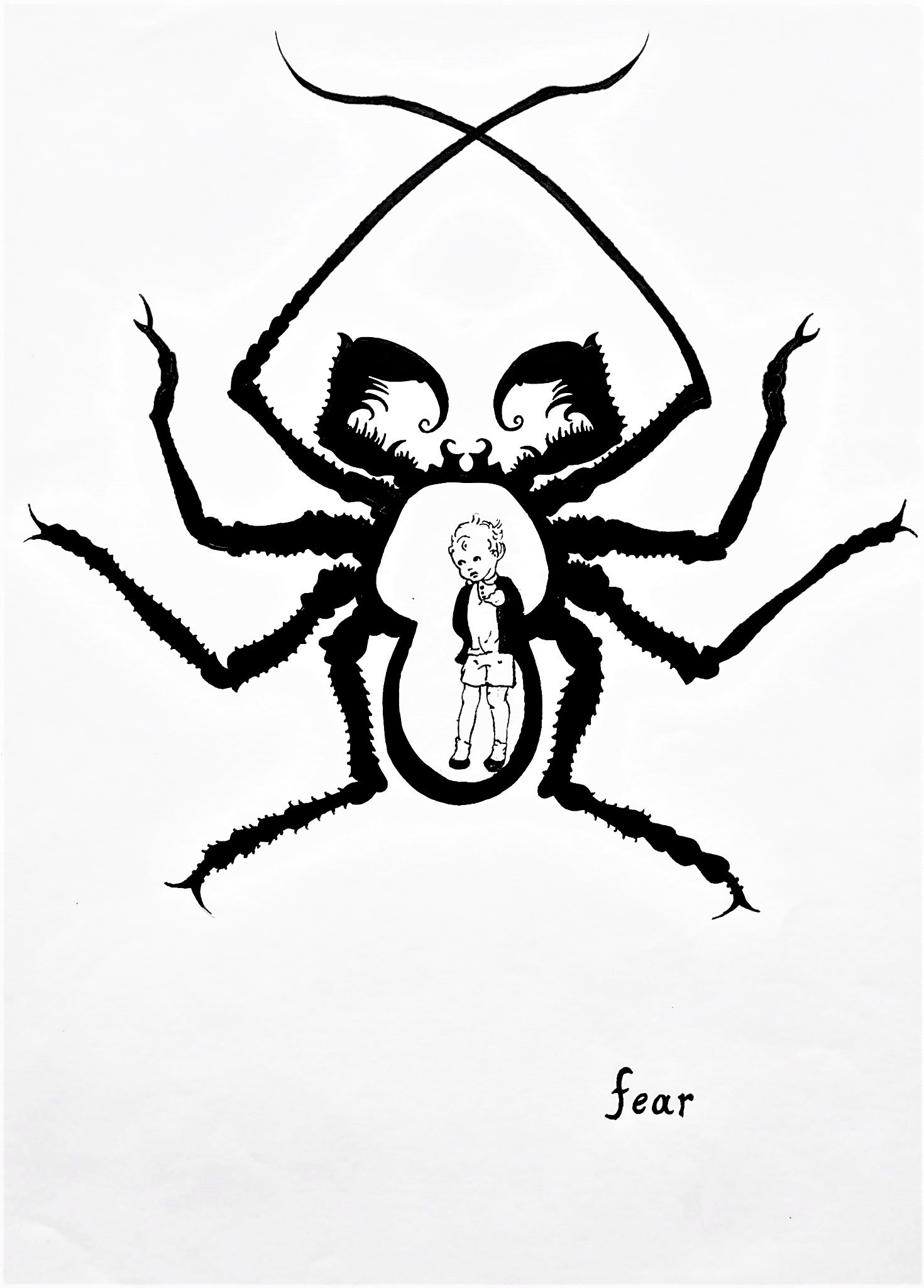

In this era of pandemic and increasing authoritarian governance, our “death-fear” makes us vulnerable to the predatory nature of capitalist venture and the controlling power of others; Terror Management Theory (TMT) proposes “that a basic psychological conflict results from having a self-preservation instinct while realizing that death is inevitable and to some extent unpredictable. This conflict produces terror, which is managed through a combination of escapism and cultural beliefs that act to counter biological reality with more significant and enduring forms of meaning and value.” - Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Jeff Greenberg and Sheldon Solomon

Ernest Becker argues most human action is taken to ignore or avoid the inevitability of death.

It is this premise that forms the basis for TMT. TMT provides a framework by which we may seek to understand the anxiety experienced by individuals, communities and societies regarding death and mortality. It also provides insight into how such primal fear can be used to control and manipulate in a commercial and political capacity.

Themes on death, dying and mortality have woven their way through my artwork since its earliest incarnations.

Our relationship with mortality has been the subject of countless philosophical works, sculptures and paintings, songs and poems, cults and religious rituals, sacraments and prayers; it is also our greatest point of avoidance.